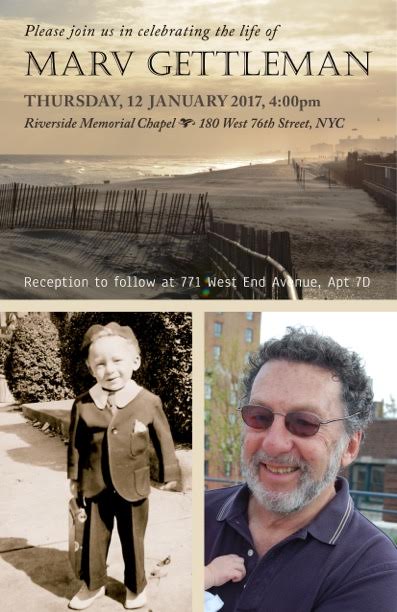

Marvin E. Gettleman

September 12, 1933 – January 7, 2017

I think of Marv as the exemplary radical historian. Long before anyone else, he understood what it meant to be “public, political, and popular,” our motto at the Radical History Review, the goal towards which we strive. Over nearly fifty years, Marv hit that mark over and over, a remarkable achievement. He made the practice of doing history historically consequential.

I met Marv 25 years ago, when I interviewed him for my book in Cuba. He had led a group of skeptical students there in summer 1960, and afterwards became a leader of the Student Fair Play for Cuba committee at City College. As always, Marv got there early, and effectively. Back then, I knew him because, as a CISPES activist, his collection, El Salvador: Central America in the New Cold War was key to our work--it was what we gave people to read.

What I didn’t know then was that the El Salvador (and Guatemala) collections of the 1980s were part of a longer trajectory of movement-building. I was too young to remember his remarkably prescient volume from 1964, Vietnam: History, Documents, and Opinions on a Major World Crisis, which became the documentary bible for the antiwar movement of that time, with hundreds of thousands of copies in print.

And when it came time to rebuild the antiwar movement again, in 2003, Marv was there helping to found Historians Against the War, producing the first pamphlet with Stuart Schaar, an Annotated Bibliography of English-Language Sources and Studies on The Middle East and Muslim South West Asia, and playing a major role for six years on our Steering Committee. As the HAW statement written by Rusti Eisenberg says, “Marv brought to our collective work decades of experience in struggles for peace, human rights and social justice. His energy, optimistic spirit and wisdom enabled us to form a strong organization of historians, offering clear opposition to the Iraq War and other US military interventions in the aftermath of 9-11.

Marv combined the militancy of an activist, tempered by a life of scholarship and reflection. In discouraging times, he was a fountain of good ideas. And when frustration nurtured excess, his was the voice of common sense.

Though a profound critic of the social order, he did not give way to cynicism. And he was never too self-important to skip the necessary tasks.”

Which brings me to the present. A few months ago I decided to teach a new “Vietnam and the Cold War” course aimed at first-years and sophomores. I started looking around for the newest and best historiography, and there is plenty. But at a certain point, I thought “I need to go back to the documents; after all, in my survey, I keep using the excerpt from General Giap’s People’s War, People’s Army and Colonel Robert Heinl’s 1971 article, ‘The Collapse of the Armed Forces.’” So for my new course starting next week, I ordered the book from which those documents are drawn, Marv’s 1995 Vietnam and America (on which he collaborated with Marilyn Young and Jane and Bruce Franklin). Marv is still there, with us, doing the long, patient work of radical history. Presente, companero.